In April 1518, pregnant with her sixth child, Katherine of Aragon visited St. Frideswide’s Shrine in Oxford with a desperate prayer for God to give her a healthy male child.

Had God chosen to answer that prayer with a live prince, history would have been different.

Instead, in November, Katherine delivered a stillborn daughter. It would be her last pregnancy. Only the infamous Mary survived, and as everyone who has ever studied British history knows, Mary was not enough for King Henry VIII and the Tudors’ tenuous claim to the English throne. Over the following decades, the English monarch demonstrated that he was willing to burn down the very religious infrastructure of his country, if only to get the boy he wanted.

By the time Henry VIII got his infant prince, the king had gone through three of his six wives, murdered many of his closest friends and advisors, and excommunicated his entire country from the Catholic Church. The consequences of Katherine’s unanswered prayer could not have been more dramatic.

Thomas Abell Research

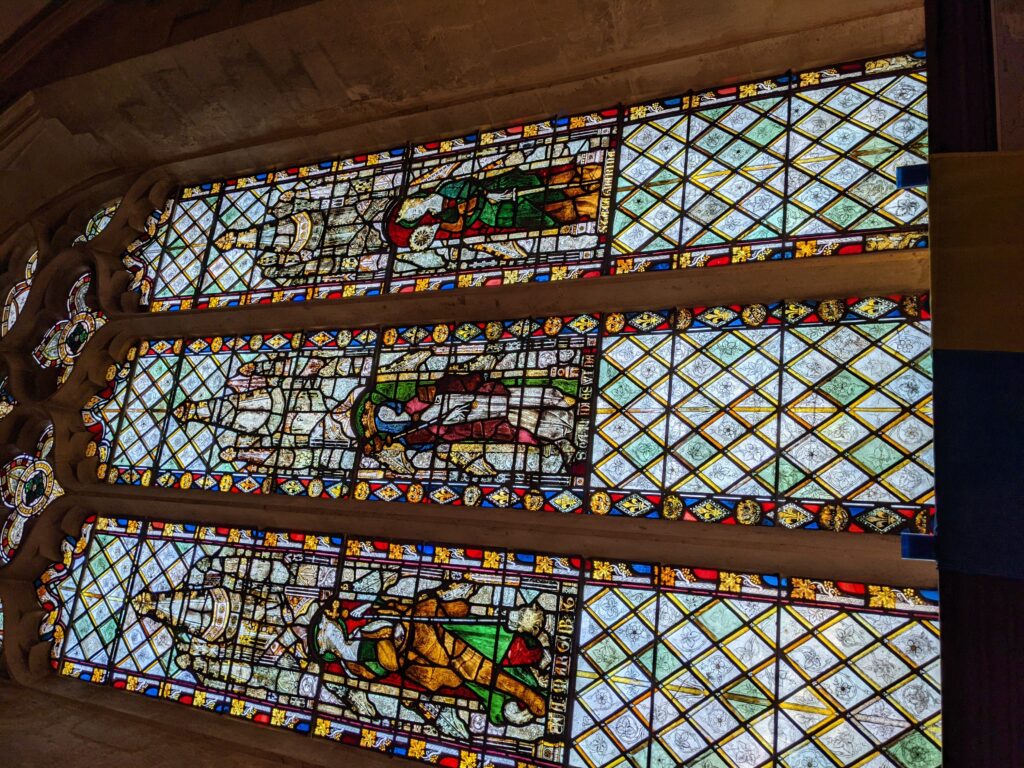

When I began researching the Thomas Abell story in September, I visited Christ Church in Oxford and saw Saint Frideswide’s Shrine, which stands today in a less frequented corner of the cathedral. What remains of the shrine Katherine visited in 1518 has been reconstructed with some of the original salvaged pieces. It sits in the middle of a room surrounded by stained glass windows depicting Frideswide’s story.

Shortly after Katherine’s visit, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey seized the priory and used the land to found his own short-lived Cardinal’s College. After Wolsey’s fall from grace, Henry VIII took on the project, creating King’s College, which was also short-lived, only to be later refounded as Christ College, which continues today as part of Oxford University.

During the English Reformation, iconoclasts looted and destroyed nearly all of England’s catholic shrines, including Frideswide’s shrine; however, pieces of it were recovered in the 19th century and moved to the cathedral where the shrine was reconstructed. What remains today is a polished limestone pedestal with older inset stonework and modern columns supporting an original 13th-century structure. It is left to the imagination to envision the bejeweled casket that once rested atop the structure, allowing devotees to pray and possibly even prostrate under Frideswide’s bones.

For my story, I have chosen to include a fictional scene based on the historical fact of Katherine’s visit in 1518. At this time, Thomas Abell, who had recently graduated from Oxford University two years prior, was still in Oxford, serving as a secular priest or pursuing his Ph.D. (Several contemporaries call him a doctor, but to my knowledge, there is no known evidence of Thomas Abell graduating with a Ph.D.)

In my story, I have chosen to place Thomas Abell in the priory to introduce him to Katherine and the pain of her story. It is one of the many creative decisions I have made in this manuscript that falls under the category of historically possible, although perhaps not probable.

We do not know from history exactly how, when, and why Thomas Abell left Oxford to join the queen’s service, but knowing that she experienced a pivotal moment in Oxford, at a time when Thomas Abell was likely also in Oxford, made me want to include it.

Who was St. Frideswide?

When I visited Christ Church, the very knowledgeable cathedral verger, Jim Godfrey, showed me the shrine and explained Frideswide’s story. Although Oxford’s patron saint is given scant attention these days, her story was once an important local narrative that informed English religious identity.

Later, as I was visiting the shrine with my four-year-old niece, who was obsessed with Frozen, I couldn’t help but look up at the images of the young women immortalized in stained glass, and think about the role Frideswide and other Saints must have played in the imagination of girls a few centuries ago. These female Saints forgoing marriage to serve the poor and pray for miracles were the Disney princesses of the Middle Ages, heroines whose legends were bigger than life.

Jackie Holderness, the Christ Church Cathedral’s educational officer, wrote a delightful children’s version of St. Frideswide’s story, The Princess Who Hid in a Tree which she read to a YouTube audience during Covid-19 lock downs.