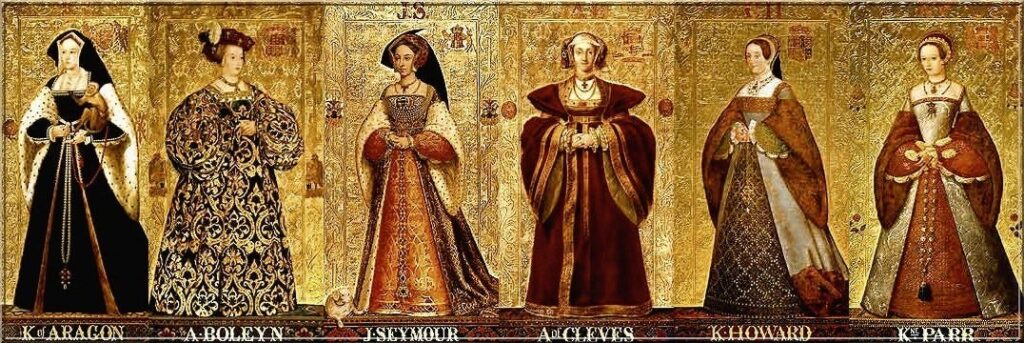

You don’t have to be an Anglophile to know King Henry VIII had six wives. Even in American schools, many of us memorized the little ditty: “divorced, beheaded, died, divorced, beheaded, survived.” The rhyme helps keep the fate of Henry’s wives straight, but it does little to reveal the complex story behind the man who ushered in the English Reformation.

Unlike German theologian Martin Luther, no one can call King Henry VIII’s motives noble or even theologically oriented. He wanted political freedom from the church’s governing body, so between 1531-33, he began increasingly exerting his authority over the church in England to the exclusion of Rome. The Pope, of course, returned the favor and excommunicated King Henry VIII in 1538.

Despite the significant religious implications of Henry’s reign, it seems to me that the vast majority of books and Netflix mini-series devoted to his story focus on the sensual details of his sex life. After all, the king was married six times and had multiple mistresses. But I don’t think this should be the focus of the story.

In my novel, Thomas Abell finds himself in the middle of King Henry’s drama, in both his efforts to divorce his wife Katherine of Aragon and extricate himself from Rome’s authority. Historically, we know that Thomas came down on Katherine’s side. He spent the last seven years of his life in the Tower of London because of his loyalty to her and his opposition to the king. But his views on the theological aspects of the English Reformation are left a bit more up to speculation.

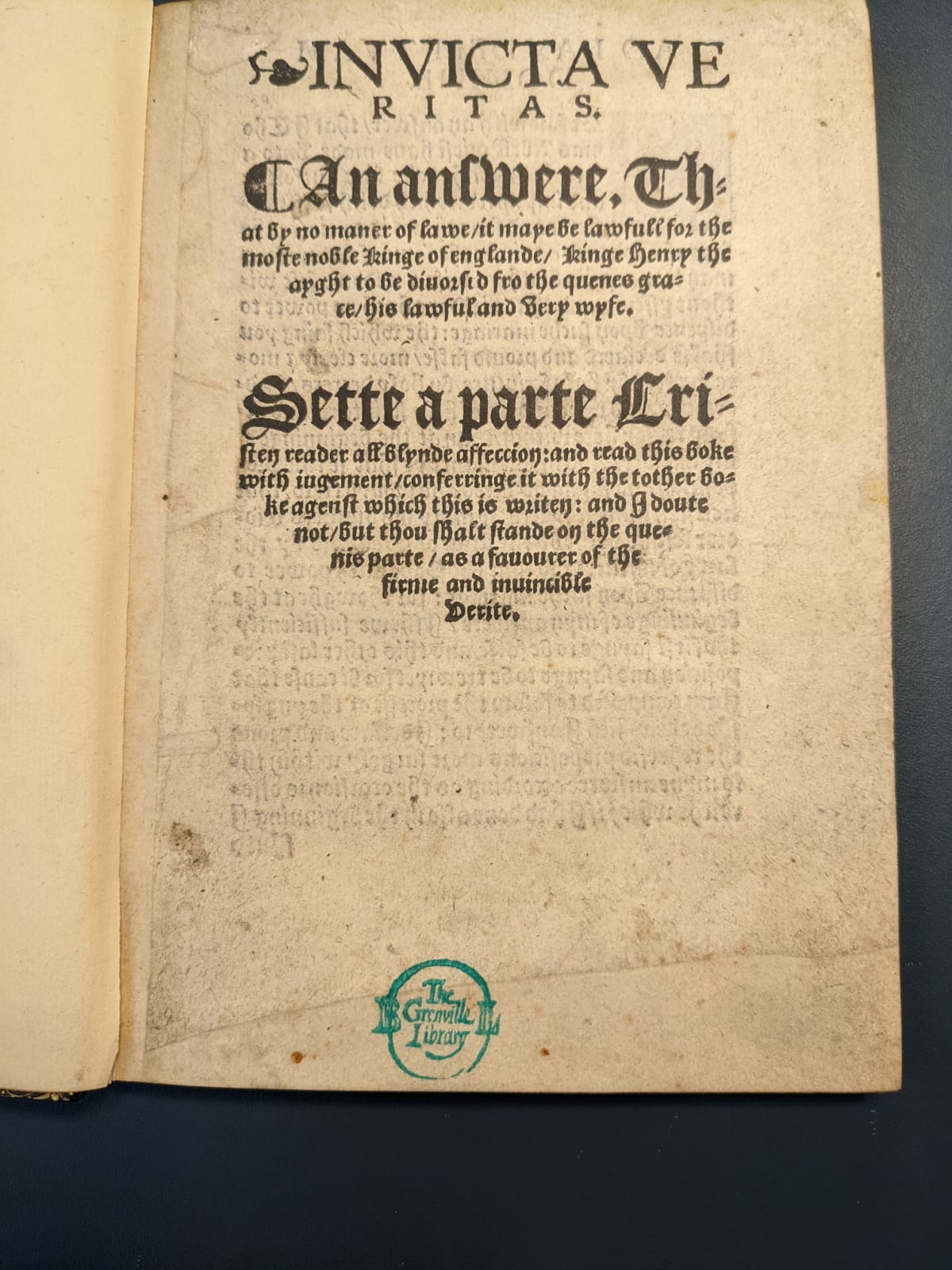

We know of Thomas from letters about him from the Spanish Ambassador Eustace Chapuys and correspondence between Thomas Abell and Thomas Cromwell and between Thomas Abell and another imprisoned priest, John Forest. But in my historical research, I have found the most significant insight into Thomas Abell’s personality from reading his own words in the booklet he published in 1532, “Invicta Veritas,” which outlined his response to leading European theologians who argued that King Henry’s marriage to his brother’s widow was against the laws of God and nature.

Having read the book, which is available in the British Library in London, I noticed that Thomas’s arguments are laid out with the logic of an academic writer or attorney. This is true, and this is true, and that is why this is true. He uses scripture and historical church doctrine to counter the theologian’s claims. It is a bit wordy at times and seems to make liberal use of the myriad of ways to spell English words in the 1530s. But it is readable and understandable. And it is dripping with Thomas’s indignation that theologians loyal to King Henry intentionally twisted scripture to make it say what the king wanted it to say.

In effect, Thomas Abell says over and over, “How dare you call good evil and evil good.” It has all the energy of an Old Testament prophet. And reading against the grain, the book is not only a defense of Katherine’s marriage to Henry but also Biblical authority, something that modern Evangelicals associate more often with the Reformation in this period.

The Reformation

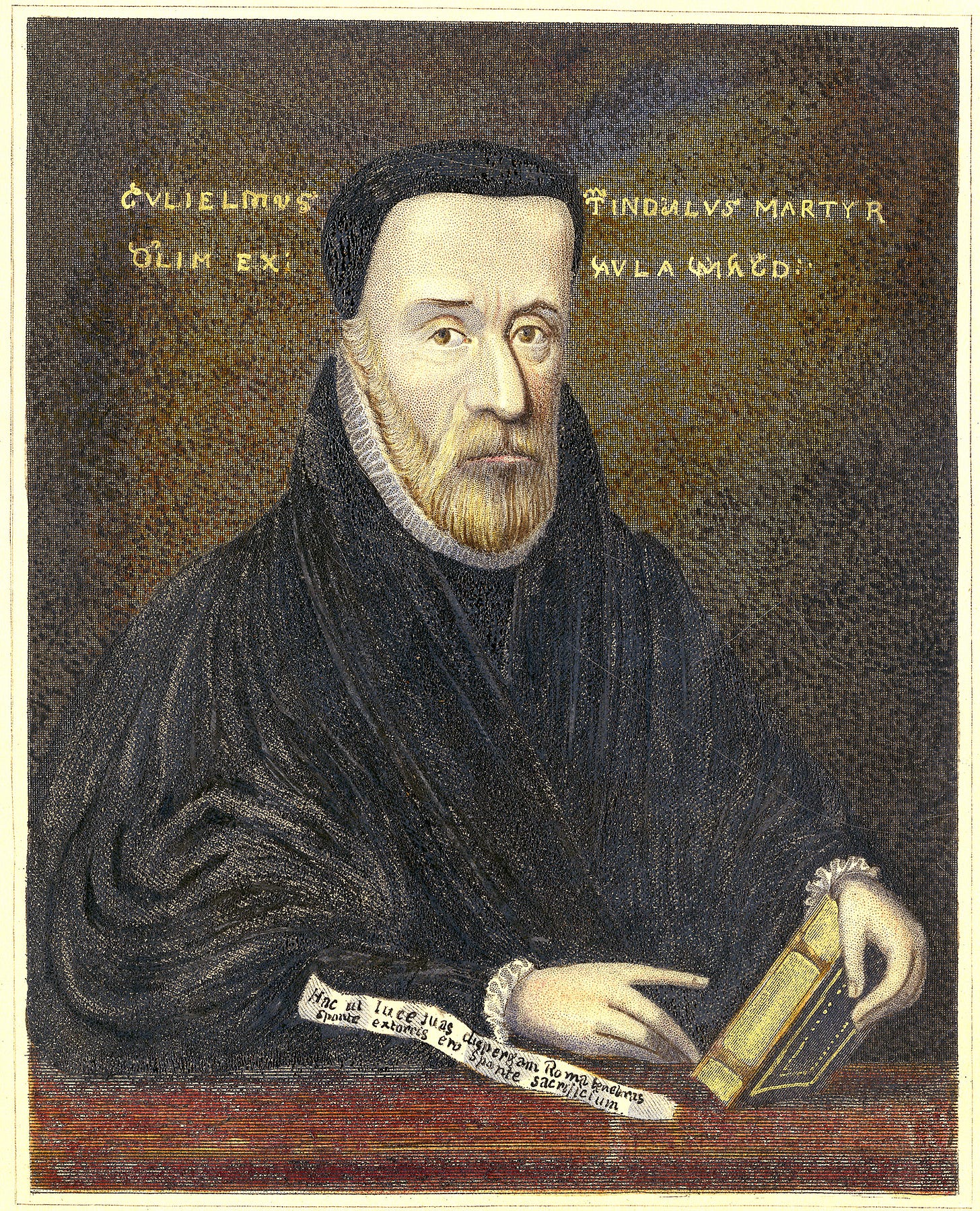

As I thought more about this, it occurred to me that even though Thomas Abell never publicly recorded his thoughts about the reformation in Europe or Martin Luther’s writings, he had to have been aware of them. He was an Oxford academic, attending during some of the same years that William Tyndale attended school there. Indeed, he would have been involved in many conversations about the hot theological issues, even years before he found himself in the queen’s service.

There is no doubt that Queen Katherine was faithfully Roman Catholic. Her parents, Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, were notoriously Catholic, initially instigating the Spanish Inquisition in 1487 to ferret out Jews and Muslims who had publicly converted to Christianity but retained their previous beliefs. There is no doubt that Ferdinand and Isabella’s commitment to orthodox catholic views significantly shaped Katherine as she grew up in the Spanish royal household.

Thomas Abell seems to have had respect for Rome in general. Invicta Veritas demonstrates a clear, detailed understanding of church canon law concerning Katherine’s case. Still, there is no conversation I could discern around the controversial topics of the ongoing Reformation, including the concepts of purgatory, indulgences, praying to saints, transubstantiation, relics, etc. The book does not seem to address any of these. (Although I am sure a better religious historian than myself might pick up on things that I missed.) But, in my view, Thomas focuses on his point that King Henry and Katherine were lawfully married, and it would be wrong to use scripture to argue that their marriage was a sin.

As for my story, I have tried to place Thomas in a historically accurate mid-Reformation England, but I also gave him a relationship with William Tyndale and other protestants as I think this is historically probable also. In fact, when Thomas Abell was executed on July 30, 1540, he was killed with two other Catholic priests and three protestants. Some historians have suggested this was King Henry’s way of exerting his dominance over both groups. Others have suggested that he intended to humiliate both groups by placing them on equal footing in the execution. But I saw no reason for this to be humiliating to Thomas if he had friendships with Protestants.

Of course, there is no hard evidence that Thomas Abell had a personal relationship with William Tyndale or any other Protestant. But the fact that he and William Tyndale attended Oxford around the same time and shared a lifelong interest in languages makes a personal relationship possible.

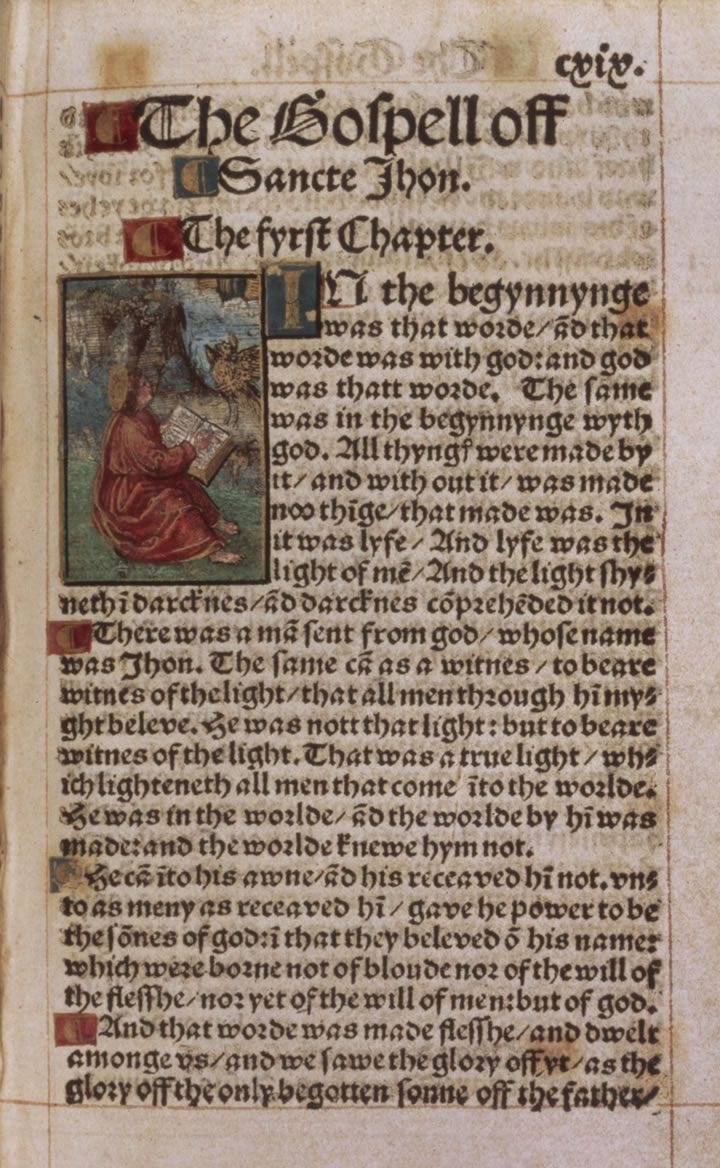

But one more interesting piece of evidence could support a possible interaction between the two men. Both Thomas Abell and William Tyndale used the same printer in Antwerp, the famous Merten de Keyser, for their books opposing King Henry.

Tyndale’s Gospel of John. Early copies of his New Testament were printed in Cologne, but Merten de Keyser published his later edition in Antwerp.

In addition to his translations of scripture, William Tyndale also wrote a book opposing Henry VIII’s efforts to divorce Katherine. In fact, it was this book, The Practice of Prelates, that angered King Henry, who demanded that Emperor Charles V extradite William Tyndale to face trial in England. Interestingly, Charles V, the same Charles V who presided over Martin Luther’s famous trial at the Diet of Worms, denied King Henry’s request, possibly suggesting his opposition to Henry’s divorce was greater than his opposition to Protestantism.

So, given all of this interaction between Protestants and Catholics, even over the matter of King Henry’s desire to get a divorce, I think it’s safe to say that it was more than a mere sex scandal. The entire episode was about power and authority. Henry VIII saw his ability to choose his own wife, again and again presumably, as his Sovereign right. But for Thomas Abell and William Tyndale, the king’s right was tempered by his obligation to God.

As a modern reader, it can be difficult to understand Thomas Abell’s passion to oppose Henry VIII’s divorce. It is simply outside of our sense of right and wrong. Americans and Europeans generally believe that if one person in a marriage desires to be released from their marriage vows, it’s best to let them go gracefully. In fact, it is difficult to imagine any modern government attempting to restrict a person’s right to get a divorce, king or not.

So why would Thomas and so many others stand in the way of King Henry’s divorce? Some writers suggest that those who opposed Henry’s divorce did it out of loyalty to Katherine as a person, and while that was indeed part of the motivation, I think it was only the beginning.

Stay tuned. I’ll explore Thomas’s rationale for opposing the divorce in next week’s newsletter. In the meantime, please leave comments. I would love to hear your thoughts on this 500-year-old controversy.