Visitors to London’s most popular historical site, the Tower of London, have heard stories of the fortress’s sordid past. On any given day, the black square-hatted Yeomen Wardens, the “Beefeaters,” roam the castle complex, ready to entertain curious tourists with tantalizing tales of imprisonments and executions.

It’s a bawdy version of history, but the basic facts are true. London Tower was the last residence for many nobles, particularly during the Tudor period.

Anne Boleyn spent her last days in the Tower, as did Henry VIII’s fifth wife, Catherine Howard, and the unfortunate Lady Jane Grey, who ruled England for a mere nine days. A host of King Henry VIII’s former friends also spent their final hours in the Tower, including the king’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, and the philosopher Thomas Moore. And that is just the beginning.

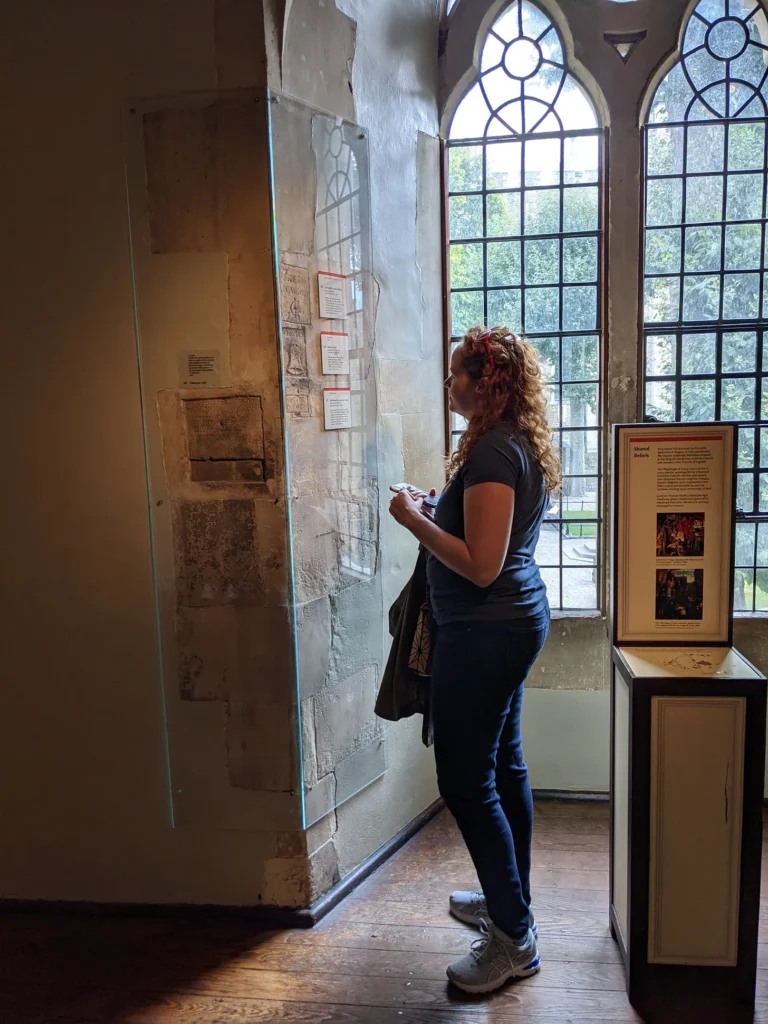

In the spacious upstairs chamber of the Beauchamp Tower, overlooking Tower Green and the central, 1,000-year-old Norman keep, the stone walls are etched with the names and messages of dozens of prisoners who lived within its confines. One of the earliest and most prominent of the prisoner graffiti is a bell carved into the wall with the letter A in the middle and the name “Thomas” boldly written in all capitals above. It’s the work of Thomas Abell, who lived alone in that room for nearly seven years until his execution in 1540.1

Thomas Abell was a Catholic priest and personal confessor to King Henry VIII’s first wife, Katherine of Aragon.2

Although Abell was never formally charged and tried, he was presumably arrested for his public support for Katherine and her right to be queen. The parliamentary act of attainder, which stripped him of his civil rights and eventually sent him to his execution, charged him with treason.

Eight years earlier, in 1532, Thomas Abell published a scathing rebuttal of Europe’s leading theological academics who had argued that King Henry’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon was against the laws of God and nature. Using the same biblical texts the other theologians had used, Thomas effectively argued that the king’s marriage to Katherine was not contrary to the teachings of the Bible. Thomas boldly entitled his book “Invicta Veritas,” The Unconquerable Truth, and wisely published it outside England in Antwerp.

In response, King Henry bought and burned as many copies of the book as possible to silence his critics. However, two copies of the book survived, including one available to the public at the British Library in London.

Thomas’s bold support for Katherine was likely something that grew over time. In fact, it is possible that King Henry VIII assumed Thomas Abell was one of his loyal supporters when Cardinal Thomas Wolsey brought Abell into the queen’s household sometime before January 1529.

In the years leading up to the king and queen’s separation, as their relationship deteriorated, the king replaced the queen’s Spanish staff with English priests and ladies in waiting.

In my novel, I have the king’s right-hand man, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, handpicking Thomas to be Katherine’s chaplain. Wolsey assumes that, as a Spanish-speaking, Oxford-trained English priest, Thomas will be loyal to the king and report Katherine’s state of mind to him. Wolsey hopes that Thomas will help him convince Katherine to comply with King Henry and retire quietly to a nunnery.

Of course, Katherine has no intention of renouncing her marriage, mainly because the move would disinherit her only living child, Mary, and make her an illegitimate daughter. She digs in her heels and fights the annulment process until the day she dies in exile.

Thomas seems to have been silent about his own convictions, making Queen Katherine distrust him, assuming quite correctly that he was a spy for Wolsey. But Thomas’s allegiances seem to shift when Cardinal Wolsey sends him on a covert mission to Spain to retrieve a unique document from the queen’s nephew, Emperor Charles V.

The document was the original papal brief explicitly granting Henry and Katherine the Church’s permission to marry, even if Katherine had consummated her marriage to Henry’s older brother, the long-dead Prince Arthur. Thomas Abell surmised that Cardinal Wolsey wanted the original document brought to England to be destroyed or kept out of the evidence file, should the royal couple’s marriage question be decided by a papal court.

Acting as a bit of a double agent, when Thomas Abell arrives in Spain, he secretly informs Emperor Charles V that the queen does not want him to send the document back to England. Instead, he advises Charles V on how he can support Katherine’s cause.

Cardinal Wolsey and King Henry do not immediately become aware that Thomas has subverted the mission to Spain, and in fact, there is no evidence that they ever learn of it as Thomas was never charged in connection to that event.

However, as time goes on, Thomas must feel the need to speak up about his own convictions. So by the time he is arrested the second time in 1533, he has been accused of speaking publicly against the king’s divorce and encouraging the queen’s household staff to continue addressing her as Queen Katherine.

The bell that Thomas carved into the Tower wall was, and still is today, a known Abell family symbol, a light-hearted pun on the unusual surname. But as Thomas carefully carved it, placing his first name like a banner over the bell, he must have also thought about the purpose of a bell, a musical instrument used to wake people up, to call them to worship, to alert them to danger in times of peril, to remind them of God. Perhaps he even heard church bells ringing as he stood and carved his name. I cannot help but wonder if he was placing his mark, setting it in stone, carving his identity as an Abell, a ringer of truth. And that was a comfort he kept through his imprisonment. He may have forfeited his life, but he kept his identity.

And I think that is a story worth telling.